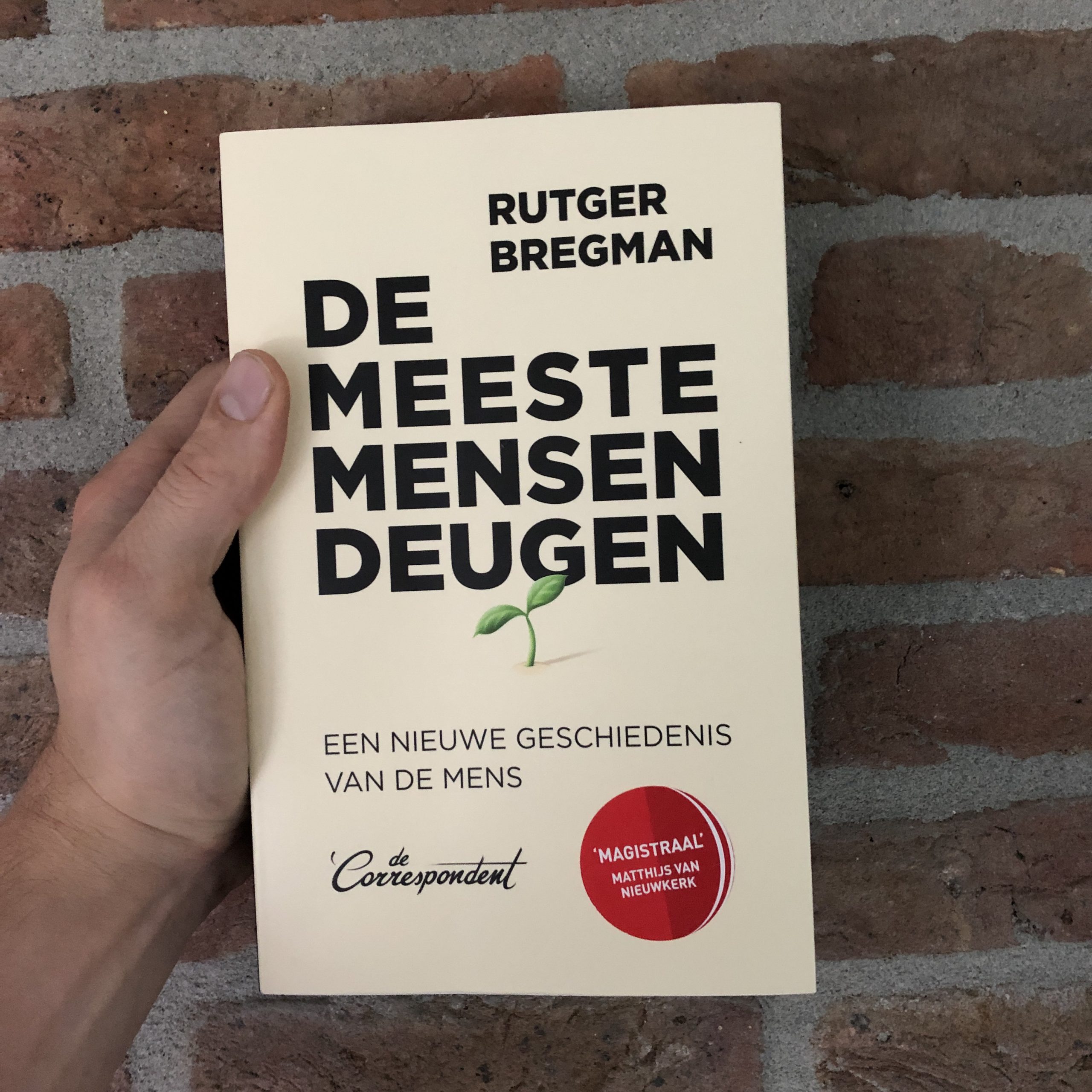

I don’t know what the English title translation for Rutger Bregman’s latest book will be. But I do know two things. One: there will be one. And two: it will be a bestseller. I do know now, and yes it will be a bestseller:

The title will be something along the lines of: Most People Are Decent. Which is a terrible translation by me and I hope they come up with something better, but it is the general premise of the book.

Bregman hails from the school of Malcolm Gladwell (who he mentions many times). He is a great storyteller, very easy to read and he is able to create a riveting narrative — from different anecdotes and studies — around a compelling sociological thesis. Overall this book sends a message of hope, which is greatly needed. So I can definitely see this book becoming an international bestseller.

To my surprise I was already familiar with most of the ideas, because I am a loyal listener of Bregman’s podcast. His writing style is very similar to his speaking style (which is not always a good thing, but in this case it is). And having listened to him for more than 30 hours, I think I read this book in his voice.

Gripes

However, even though I can agree on many things (like ‘following the news is bad for you’), there are still a few gripes I have with the book. (Not included the paradoxical reality that I probably disagree with the general premise but completely wholeheartedly agree with the conclusion of the book.)

Dissecting studies

Bregman is not a scientist, he is an investigative historical journalist, and a really good one. He has a keen nose for pointing out flaws in scientific studies and plotting them against historical backgrounds. And the conclusions he draws from those are seemingly valid. And he makes a good case for most of them, but here is the thing:

Pointing out something is wrong doesn’t directly make the opposite true.

And even though the opposite might very well be true, that is not how science works.

Sometimes such a conclusion makes perfect sense (i.e. I will not argue the correctness of the Stanford Prison Experiment), but in other places I think Bregman lets the narrative prevail the validity of the argument. Which — again — might still be true, but is not necessarily backed up by evidence (this mostly being the case with the Steven Pinker study, I think).

And sometimes the proof or argument is more anecdotal and the sample sizes too small to take for granted. But I also think Bregman is well aware of this. Because this is exactly what he does himself — pointing out flaws. Also he is well aware that history is in the eye of one who tells it and that today’s earth-shattering scientific study can be tomorrows scrap paper. Just something to keep in mind.

Factual fallacies

There is one in particular I can’t not point out, because it is one of those persistent false claims that are constantly being regurgitated. And because in this case it is about my hometown, I feel I need to address this one.

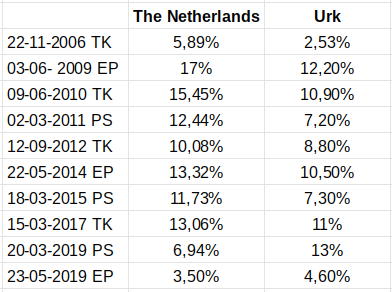

In a throwaway sentence on page 432 Bregman argues that my hometown — Urk — consistently has the most PVV (a far-right party) voters. Sure, it helps the narrative, but I would argue this is false. Have a look at the last 10 (!) elections. There is only one election where Urk voted definitely higher — and one time marginally higher — but in all other elections Urk voted structurally lower for the PVV in comparison with the national vote.

I would not call this consistently higher (sources: Google and Wikipedia)

This is not meant to point out that the book or the premise is wrong. This is just one small example of keeping your eyes and ears open and to always keep thinking for yourself.

Gladwell

I think I have read everything by Gladwell, except his latest. And I think Bregman is also a fan. And he will probably be called the Dutch Gladwell when this book becomes that international bestseller. An unimaginative title (though arguably better than ‘that Davos guy’), but more importantly maybe also a wrong one.

Because Gladwell is under a lot of fire lately, mostly because he tends to oversimplify in an effort to push his conclusions. And I think Bregman does steer clear of this. He is much more careful in drawing conclusions, and doesn’t shy away from casting doubts on his conclusions. Which makes the reader part of the process. But he does call for a grandiose idea (A New Realism) which is another thing where Gladwell usually misses the target. But in Bregman’s case this grandiose idea follows naturally and is commendable.

Overall

Having stated some gripes, know that I am not a miser (just a stickler for facts), and I can safely say this is a wonderful book!

Bregman is not an optimist, nor a pessimist but a possibilist (yes, I borrowed that from the book). And I like that a lot! And I don’t know if Bregman knows this, but his ten rules from the last chapter share a great resemblance to Covey’s seven principles. Which I also greatly endorse.

And while this is not a scientific book, it is a book about hope, ideas and presenting a different perspective. And like I have stated many times before on my blog: getting a different perspective is always a good thing. So I would definitely recommend reading this book.

Side note 1: the effect of a cover sticker (to me) has probably the opposite of the intended effect. Because the TV program (where the sticker is from) needs the writer as much as the writer needs the TV program. And when I read on page 28 that Bregman himself calls a different book ‘magistraal’: it makes it even more lazy or at least ironic. So to me such a sticker is a warning: always make up your own mind.

Side note 2: from all the books I read this year, this was probably my favorite physical copy. Though not a hardcover, it was just the right size, the cover design is gorgeous and the font and typesetting are absolutely perfect! Of course, it also helps that Bregman is a great writer, but the overall design also make this book a pure delight to hold and read. I wish all my books were like this.

Pingback: In Dubio - Rob Wijnberg - piks.nl