The inception of Git (2005) is more or less the halfway point between the inception of Linux (1991) and today (2019). A lot has happened since. One thing is clear however: software is eating the world and Git is the fork with which it is being eaten. (Yes, pun intended).

Linux and Git

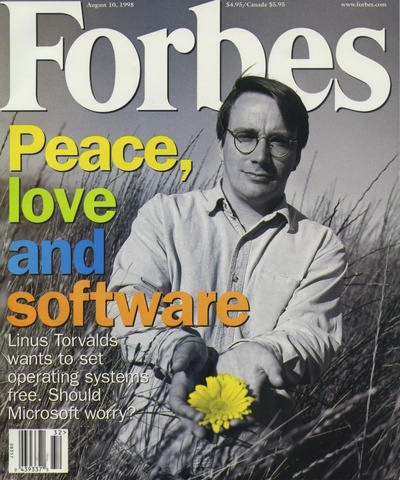

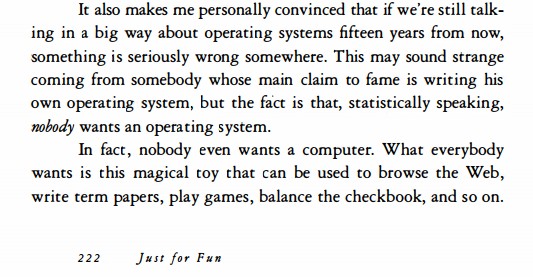

In 2005, as far as Linus Torvalds’ legacy was concerned, he didn’t need to worry. His pet project Linux — “won’t be big and professional” — was well on its way to dominating the server and supercomputer market. And with the arrival of Linux powered Android smartphones this usage would even be eclipsed a few years later. Linux was also already a full-blown day job for many developers and the biggest distributed software project in the world.

However, with the creation of Git in 2005, Linus Torvalds can stake the claim that he is responsible for not one, but two of the most important software revolutions ever. Both projects grew out of a personal itch, with the latter being needed for the other. The story of both inceptions are of course very well documented in the annals of internet history i.e. mailinglist archives. (Side note: one of Git’s most impressive feats was at the very early beginning, when Torvalds was able to get Git self-hosted within a matter of days 🤯).

Today

Fast forward to today and Git is everywhere. It has become the de facto distributed versioning control system (DVCS). However, it was of course not the first DVCS and may not even be the best i.e. most suitable for some use cases.

The Linux project using Git is of course the biggest confirmation of Git’s powerful qualities. Because no other open source projects are bigger than Linux. So if it’s good enough for Linux it sure should be good enough for all other projects. Right?

However Git is also notorious for being the perfect tool to shoot yourself in the foot with. It demands a different way of thinking. And things can quickly go wrong if you’re not completely comfortable with what you’re doing.

Web-based DVCS

Part of these problems were solved by GitHub. Which gave the ideas of Git and distributed software collaboration a web interface and made it social (follow developers, star projects etc.). It was the right timing and in an increasingly interconnected world distributed version control seemed like the only way to go. This left classic client-server version control systems like CVS and SVN in the dust (though some large projects are still developed using these models e.g. OpenBSD uses CVS).

GitHub helped popularize Git itself. And legions of young developers grew up using GitHub and therefore Git. And yet, the world was still hungry for more. This was proven by the arrival of GitLab, initially envisioned as as SaaS Git service, most GitLab revenue now comes from self-hosted installations with premium features.

But of course GitHub wasn’t the only web-based version control system. BitBucket started around the same time and offered not only Git support but also Mercurial support. And even in 2019 new web-based software development platforms (using Git) are born: i.e. sourcehut.

Too late?

However the fast adoption of tools like GitHub had already left other distributed version control systems behind in popularity: systems like Fossil, Bazaar and Mercurial and many others. Even though some of these systems on a certain level might be better suited for most projects. The relative simplicity of Fossil does a lot of things right. And a lot of people seem to agree Mercurial is the more intuitive DVCS.

BitKeeper was also too late to realize that they had lost the war, when they open-sourced their software in 2016. Remember: BitKeeper being proprietary was one of the main reasons Git was born initially.

Yesterday BitBucket announced they would sunset their Mercurial support. Effectively giving almost nothing short of a deathblow to Mercurial, as BitBucket was one of the largest promoters of Mercurial. This set off quite a few discussions around the internet. Partly because of how they plan to sunset their support. But partly also because Mercurial seems to have a lot of sentimental support — the argument being that it is the saner and more intuitive DVCS. Which is surprising because, as stated by BitBucket; over 90% of their users use Git. So there is a clear winner. Still the idea of a winner-takes-all does not sit well with some developers. Which is probably a good thing.

Future?

Right now Git is the clear winner, there is no denying that. Git is everywhere, and for many IDEs/workflow/collaboration software it is the default choice for a DVCS. But things are never static, especially in the world of software. So I am curious to see where we’ll be in another 14 years!